By Elizabeth Graham -February 21, 2020 2:35 am

Find the full story here.

Staying current on the frantic pace of the coronavirus outbreak means following reports by major news outlets for most people, but analysts at EpiVax Inc. are more interested in websites that share genetic sequences of the novel virus.

Chinese health officials published the sequence in late January, and within a week, a team at Providence-based EpiVax had worked out the building blocks for a coronavirus vaccine.

Any vaccine, though, faces a tough challenge from the swiftly evolving virus.

By the end of January, the coronavirus had multiplied to 40 sequences, or variations. That number was expected to continue to grow. The virus’s speedy shape-shifting mirrors its spread, which grew from 9,700 cases at the end of January to more than 73,000 by mid-February.

Despite the unpredictability, Dr. Annie S. De Groot, CEO and chief science officer at EpiVax, said her company is capable of hitting the virus head-on.

De Groot was among a team of about five people that formulated a vaccine by the end of January, and within days was ready to seek funding and partners.

“Right now, we can provide a recipe for a vaccine to any company that’s interested in making one,” she said.

‘We can provide a recipe for a vaccine to any company that’s interested.’

DR. ANNIE S. DE GROOT, EpiVax Inc. CEO and chief science officer

For a company the size of EpiVax, finding funding and the right partner is integral to producing and distributing a vaccine. It has been in touch with a number of potential partners, who are eyeing numerous organic avenues to fight the virus.

“Vaccines you can make in RNA, you can make in DNA, you can make in protein, you can make peptides,” De Groot said. “We’re talking to all of the players in all of those different vaccine platforms about making the vaccine.”

Should the virus spin off into numerous other variations, EpiVax is ready to return to the lab.

“We’ve spent 21 years preparing for the day when we would have to design a vaccine in 24 hours. We’re at that point,” De Groot said. “This is the type of virus … that like HIV, influenza and hepatitis C, mutates incredibly rapidly, so no one single vaccine is going to be effective against this new outbreak.

“There will have to be advanced tools applied in order to discern where the virus will keep its sequence the same and where it’s going to mutate,” she said. “Those are tools that we have. As more information is available, we should be able to make a decision soon about which parts of the virus are going to be the best parts to put in a vaccine, and which ones we can throw away because they’re going to mutate all the time.”

EpiVax joins major companies across the world that are racing to develop a vaccine for the virus that has now been dubbed SARS-CoV-2. Johnson & Johnson, Cambridge-based Moderna and Inovio are just a few of the labs in the United States that have said they are working on or have designed vaccines. Moderna and Inovio have received funding for the work from CEPI, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. Researchers in Germany, Hong Kong and Japan have also said they are in various stages of designing a vaccine.

Still, no matter how quickly they are completed, all vaccines need to be approved for use in humans, a process that some major companies have said could take months or even a year.

De Groot estimated that a vaccine designed by EpiVax can be ready for human use within months, but she noted that other companies are likely on the same pace.

“We could make a peptide vaccine that could be put into people in months … and that means a phase one clinical trial,” she said. “At this point, given what we’re seeing out of China, unless they’re able to quarantine the entire country, we need a vaccine in months.”

Dozens of countries have confirmed cases of coronavirus, which, with a death toll of more than 1,800 as of mid-February, exceeds that of the 2003 SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome, epidemic.

Although speed is important, accuracy is crucial, especially in an outbreak of this size, De Groot said, referencing the 2013 H7N9, or bird flu, outbreak in China that sickened significantly fewer people than SARS-CoV-2 despite its relatively high mortality rate.

A vaccine produced in the United States was not effective, De Groot said.

“Many companies are saying that they’re jumping in. They’re saying we have a platform, we’re going to make a vaccine,” she said of the coronavirus outbreak. “But how they make that vaccine is actually really important. The real question is does it work.”

Computational tools used by EpiVax researchers allow for a detailed look at virus sequences, a look that can make clear which parts of a virus could act as effective building blocks for a vaccine.

“It’s important for this particular epidemic, as we prepare to respond and make vaccines, to really be thoughtful about throwing money [at it],” De Groot said. “Are we just checking the box and saying that we’re making a vaccine that may not be effective? Because that’s not going to be enough. We actually have to make vaccines that work.”

- Researchers working in the labs at EviVax in Providence. Olivia Morin, research associate, working in their culture lab. PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO

- Researchers working in the labs at EviVax in Providence. Drasti Kanakia, senior research associate, preparing samples for analysis. PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO

- PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO

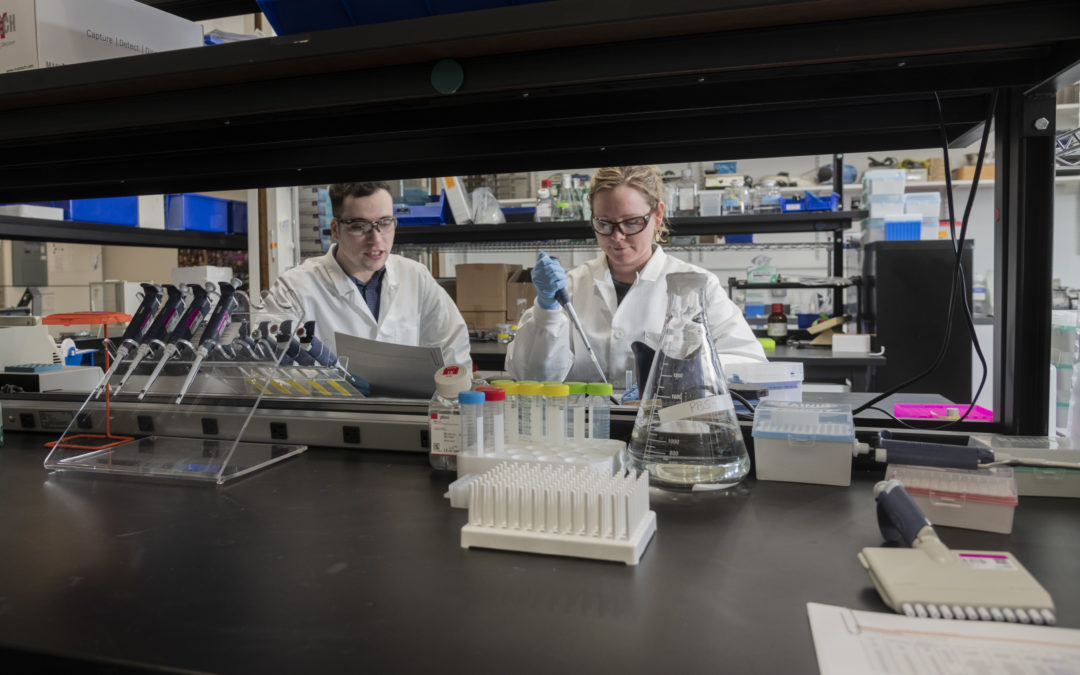

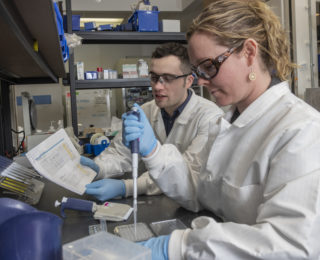

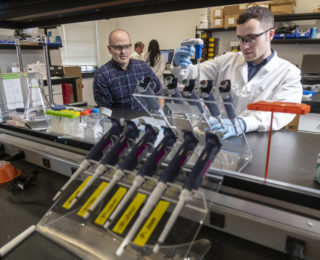

- Researchers working in the labs at EviVax in Providence. From left, Mitchell McAllister, research associate, Olivia Morin, research associate. PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO

- PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO

- Researchers working in the labs at EviVax in Providence. From left, Olivia Morin, research associate, Mitchell McAllister, research associate, working in their culture lab. PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO

- Researchers working in the labs at EviVax in Providence. Olivia Morin, research associate, working in their culture lab. PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO

- Cliff Grimm, CFO at EpiVax, Mitchell McAllister, research associate, working in the main lab. PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO

- Researchers working in the labs at EviVax in Providence. Christopher Talbot, research associate II, preparing samples for analysis. PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO

Elizabeth Graham is a PBN staff writer. Contact her at Graham@PBN.com.

Photos my Michael Salerno